Friedreich’s ataxia

What is Friedreich’s ataxia?

Friedreich’s ataxia is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative condition and is the most common type of inherited ataxia among those of European ancestry.1,2

The onset of symptoms is typically around 5–15 years of age and can include the progressive loss of coordination in the arms and legs, fatigue, muscle loss, vision impairment, hearing loss, slurred speech, cardiomyopathy and diabetes mellitus.1,2 Currently, there are no approved therapies for Friedreich’s ataxia, and the reported mean age of death is 36 years of age.1,3

Friedreich’s ataxia has a significant negative impact on a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL).4 Physical impairments that become worse as the disease progresses are a main contributor to a poor HRQoL.4

Owing to a young age of onset and the physical impairments, many patients with Friedreich’s ataxia rely on a caregiver. However, caregivers can experience a poor quality of life (QoL) too, with responsibilities negatively impacting on work or social lives, as well as mental or emotional health.5

Early and accurate diagnosis is essential for patients to receive supportive care and tailored interventions that aim to prolong independence and maintain QoL.6 Newly diagnosed patients should also receive genetic counseling to discuss implications to other family members and pre-symptomatic testing.6

What causes Friedreich’s ataxia?

Friedreich’s ataxia is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the frataxin (FXN) gene.1,7 The most common mutation in affected individuals is an alpha glucosidase (GAA) trinucleotide repeat, which accounts for the majority (96%) of patients. The remaining 4% of patients have a point mutation or deletion.1,8 Disease severity could depend on the increased number of GAA repeats leading to younger age of onset and associated symptoms such as progressive ataxia, weakness, and sensory deficits.1,7

The affected FXN gene encodes the protein frataxin.9 Frataxin is found in all cells of the body, but is highest in the heart, spinal cord, liver, pancreas and skeletal muscles.9 How mutations in FXN lead to Friedreich’s ataxia is not completely understood, but it is believed that a shortage of the frataxin protein impairs energy production in the mitochondria, resulting in affected cells not functioning properly due to low energy.9 Deficiency of frataxin leads to ferroptosis, which results in the presenting symptoms of Friedreich’s ataxia.10

What is ferroptosis?

Ferroptosis refers to an iron-dependent form of cell death.10 In Friedreich’s ataxia, the loss of frataxin caused by mutations in the FXN gene leads to dysregulation of iron regulatory proteins, which causes oxidative damage to cells.10

Furthermore, due to oxidative stress and iron overload, the mitochondria aren’t able to produce enough adenosine triphosphate (ATP), meaning cells have less energy for processes such as muscle contraction. This FXN downregulation results in neuronal degeneration and eventual ferroptosis at sites where FXN levels are high.7,10

Areas most affected include the heart and the dorsal root ganglion. Ferroptosis within these areas reflects the main pathology sites in Friedreich’s ataxia and causes common symptoms such as cardiomyopathy and limb ataxia.7,10

The estimated prevalence and incidence of Friedreich’s ataxia

The global prevalence of Friedreich’s ataxia is 1:40,000.11 It is the most common inherited ataxia in people of Western European descent,1 with an estimated incidence rate of 1:29,000 among Caucasians.12 However, there are large regional differences of incidence within Europe, with around 1 in 20,000 cases in Southwest Europe compared with 1 in 250,000 in the North and East of Europe.6 Friedreich’s ataxia also frequently occurs in the Middle East, South Asia and North Africa.11

The signs and symptoms of Friedreich’s ataxia

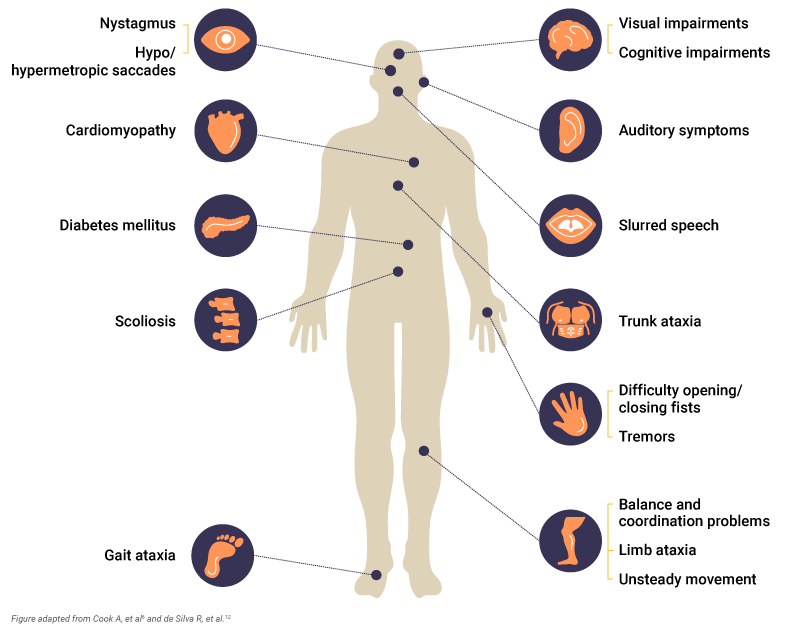

Friedreich’s ataxia symptoms normally emerge during puberty, with typical characteristics worsening with age.6 Ataxia means ‘lack of coordination’ and the most common symptoms are those that affect movement and balance. Patients typically present with unsteadiness, clumsiness and slurred speech.6,12 Gait and balance often worsen, with many patients needing a wheelchair, and speech disturbances can impair communication.12 Both the central and peripheral nervous systems are affected, as well as the musculoskeletal system, the myocardium, and the pancreas, with diabetes mellitus resulting if the pancreas is affected.6

Patients can also experience6,12:

- Gait ataxia: Develops early, and gait is unsteady for controlled movements

- Trunk ataxia: Instability of the torso, often noticed while sitting. Most patients require a wheelchair by 30 years of age

- Limb ataxia: Affects coordination and dexterity so that activities of daily living become difficult

- Upper limb dysdiadochokinesia: Inability to perform rapid, alternating muscle movements, such as opening/closing of fists or finger tapping

- Nystagmus: Rapid, involuntary movement of the eyes

- Hypo/hypermetropic saccade: Eye movements that under or overshoot in relation to the visual target

- Unsteady movement

Scoliosis is also a common early symptom that may require surgical correction.6 Other symptoms associated with Friedreich’s ataxia include cognitive impairments, cardiac complications such as cardiomyopathy, spasticity and tremors, and auditory and visual impairments.12

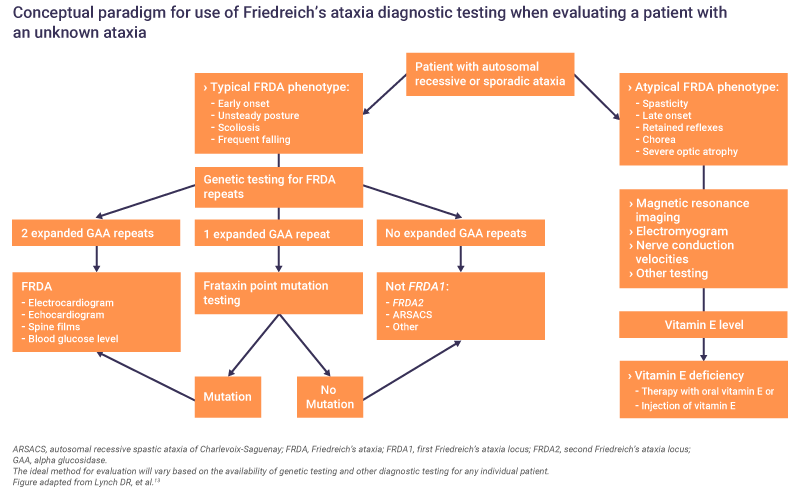

Determining a diagnosis of Friedreich’s ataxia

Diagnosing Friedreich’s ataxia can be challenging – although age of onset is around 5–15 years, some patients present as late as 60 years of age, with more severe symptoms associated with an earlier age of onset.8 As it is a recessive condition, most patients do not have a family history of Friedreich’s ataxia. Diagnosis is made by a pediatric neurologist (or a similar sub-specialist) once symptoms develop, based on descriptions of early symptoms from caregivers to support diagnostic suspicion.8

Since many of the symptoms of ataxias are treatable, timely diagnosis is important for optimal management.12 Initial diagnosis may be suspected based on reported symptoms such as slurred speech, clumsiness and unsteadiness.12

Genetic testing is critical for a definitive diagnosis of Friedreich’s ataxia and should be performed as soon as a case is suspected.8 Genetic testing allows identification of mutations in the FXN gene.8 GAA repeat testing is a core diagnostic test and confirms diagnosis in 96% of patients.8 However, in 4% of patients who do not have two expanded GAA repeats, FXN sequencing is required to identify the second mutation type.8

When a diagnosis is confirmed, further clinical and neurological assessments should be made to develop a full clinical picture.6 Since cardiomyopathy is the most common cause of death in Friedreich’s ataxia, cardiological evaluations are advised.6 If cardiac symptoms are present, or the results are abnormal, input from a cardiologist is required to determine if pharmacological intervention is necessary.6

Assessments on diagnosis can include13:

- Electrocardiography, echocardiography and other cardiological evaluations

- Nerve conduction velocities

- Spine films

- Electromyogram

- Blood glucose level

- Magnetic resonance imaging

Rating scales to identify the degree of impairment can be used to record disease progression.12 The Friedreich’s Ataxia Rating Scale (FARS) is one such scale that is specific to this disease, though more generic scales, such as the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS), are also available.12

What is the prognosis of Friedreich’s ataxia?

Patients with Friedreich’s ataxia often experience poor QoL, with worsening physical symptoms contributing to poor health-related QoL in many patients.4,5 Degenerating physical mobility alongside cardiovascular and endocrinal complications, combined with the young age of onset, means that many patients rely on a caregiver and require lifelong care.

The prognosis of Friedreich’s ataxia is variable depending on the number of GAA repeats. A high number of repeats corresponds to an earlier age of onset, more severe disease and increased complications, including cardiovascular and endocrine complications (such as cardiomyopathy and diabetes mellitus).1 Wheelchair use is typically required at an average of 15 years after symptom onset, and lifespan is significantly reduced, with the average time from disease onset to death being 36 years.1 Complications from cardiomyopathy is the most common cause of death.1

For newly diagnosed patients, genetic counseling is recommended to discuss family planning or disease implications for other family members.6 Physiotherapists and occupational therapists play a role in alleviating symptoms such as gait, weakness, and spasticity, while speech and language therapy is recommended for speech and swallowing difficulties.6

Impact on caregivers

Due to a young age of onset, and symptoms that progressively worsen, Friedreich’s ataxia can have a substantial impact on caregivers.5 Caring for a patient with Friedreich’s ataxia can affect work, school or social aspects, as well as impacting on mental and emotional wellbeing.5 Two-thirds of caregivers agree that caring for a patient is emotionally stressful, while 40% of caregivers report a negative impact on their mental health.5 Caregiver physical health can also be affected – 64% of rare disease caregivers have seen a physical decline in their own health while they care for a loved one.5

Abbreviations

ARSACS, autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; FARS, Friedreich’s Ataxia Rating Scale; FRDA, Friedreich’s ataxia; FRDA1, first Friedreich’s ataxia locus; FRDA2; second Friedreich’s ataxia locus; FXN, frataxin; GAA, alpha glucosidase; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICARS, International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale; QoL, quality of life; SARA, Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia.

References

- Delatycki MB, Bidichandani SI. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;132:104606.

- Seabury J, Alexandrou D, Dilek N, et al. Neurology. 2023;100(8):e808–e821.

- Corben LA, Collins V, Milne S, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):415.

- Figueiredo M. Worsening Physical Impairments Affect Quality of Life in FA, Study Shows. Available from: https://friedreichsataxianews.com/news/worsening-physical-impairments-significantly-affect-quality-of-life-fa-study-shows/#:~:text=FA%20is%20a%20rare%2C%20inherited,of%20life%2C%20known%20as%20HRQOL. Accessed June 2025.

- Meissner M. Help and Resources for Caregivers of Loved Ones with Friedreich’s Ataxia. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/resources-caregivers-friedreichs-ataxia#takeaway. Accessed June 2025.

- Cook A, Giunti P. Br Med Bull. 2017;124(1):19–30.

- Apolloni S, Milani M, D’Ambrosi N. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11):6297.

- Lynch DR, Schadt K, Kichula E, et al. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1645–1658.

- MedlinePlus. FXN gene. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/fxn/#conditions. Accessed June 2025.

- La Rosa P, Petrillo S, Fiorenza MT, et al. Biomolecules. 2020;10(11):1551.

- Williams CT, De Jesus O. Friedreich Ataxia. [Updated 2023 June 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563199/. Accessed June 2025.

- de Silva R, Greenfield J, Cook A, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):51.

- Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Balcer LJ, et al. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:743–747.